The basics of baseball are relatively easy to understand, but the game is a lot more fun to watch if you understand the nuances and the intricate rules. By providing this growing and ever-evolving glossary, my goal is to break down all things baseball - from rules to specifications to ridiculous clauses - with definitions that are easy to understand but not oversimplified. Any time I think of yet another aspect of the game that I don't 100% understand, I make sure to research it thoroughly and add it here, and I also love to know which rules/terms

you would like to know more about. Feel free to

give me some feedback on what you would like added here - or if you notice any errors in the existing explanations!

Recent additions: Pavano, Pecota, RISPArbitration: Arbitration gives players a chance to negotiate for more money or better contract terms. Both free agents

and players under contract can be eligible for arbitration, although players under contract must have been with the team for

at least three - but less than six – seasons. Sometimes, such as with Kevin Brown after the 2005 season, the team will decline to participate in arbitration, which ends the opportunity for a player to negotiate and sign with that team. For players that a team

does hope to negotiate with and resign, the process itself begins with his team offering him a salary, which the player then counters with a (much higher, usually) salary that he'd like to earn. Generally, the team and the player will then negotiate and hammer down a salary somewhere in between the two salaries, but if they can't settle they will bring in an independent arbitrator to decide for them. The arbitrator hears from both the player and the team and decides on a salary fair to both the player and the team.

Backloaded Contract: Often, when a team wants to secure a star player but doesn’t want to expend its entire payroll on the one player, they will arrange a “backloading” deal. These deals allow a team to pay a player a smaller amount in his first year with the team while agreeing to pay him increasingly more in subsequent years. For example, when Pettitte signed with the Astros in 2004 he was paid just $5.5 million for his first season, $8.5 million for his second, and $17.5 million for his third season in Houston.

Balk: The balk is one of the more complicated nuances in the language that is baseball. Very simply put, a balk occurs when a pitcher makes a move inconsistent with a regular pitching motion when there are runners on base. The rule serves to protect the base runners from being tricked/deceived by the pitcher (i.e., if the pitcher were to trick the baserunner into believing he was winding up for a pitch, he may be able to throw said baserunner out in an attempt to steal). The most common pitcher actions that cause umpires to call a balk include:

Baltimore Chop: A type of bunt popularized by the original Baltimore Orioles, which, as we know, turned into our own Yankees. A perfect "chop" would have the batter hit the ball downwards, as close to home plate as possible. When this is executed properly, the ball bounces high enough to allow the batter to utilize his speed and reach first base before the defense is able to make a play. This tactic was popular in the earlier days of the game, and is rarely used today.

Dropped Third Strike Rule: In baseball, as we all know, it's three strikes and yer out! But the dropped third strike rule is something of a lucky loophole for a batter. If the catcher fails to catch the third strike ball, the batter is not out as he usually would be. He officially becomes a baserunner and is not out until he is either tagged out or thrown out at first. In other words, a batter can strike out but still make it to first base if the catcher drops the ball (literally) and doesn't tag him or throw it to first in time. This rule became notorious during the 2005 ALCS, when A.J. Pierzynski took advantage of an apparent dropped third strike, and went to first base while the Angels defense assumed he had struck out and did not try to make a play.

As with all baseball rules, there are always nuances to complicate things! Most importantly, first base must be unoccupied, OR, if it

is occupied there MUST be two outs. Another interesting condition to keep in mind while keeping score is that if the batter doesn't realize that he has become a baserunner and heads back towards the dugout, he isn't technically "out" until he actually reaches the dugout steps.

Fielder's Choice: Usually, when a ground ball is hit to the infield, a fielder will throw to first to get out the batter. However, if there are runners on base, the fielder might instead decide to throw to another base to throw out the lead runner. In this case, even though the batter got to first base safely (because the fielder chose to throw out another guy at 2nd, 3rd, or home instead), he is not credited with a hit.

Ground Rule Double: Technically, a "ground rule double" is a double awarded by the umpire because a fair ball became unplayable according to the ground rules at the ballpark (like a ball getting stuck in the ivy at Wrigley Field). More commonly, though, the term is used to describe any double awarded after a fair ball bounces over a fence or other boundary. When an umpire awards a ground rule double, the batter goes to 2nd base (obviously) and every baserunner is allowed to advanced precisely 2 bases. A runner from first base is thus required to stop at third, even if he obviously could have scored had the ball not gone out of play.

Hit-and-Run Play: An offensive move done in hopes of avoiding a double play when there is a runner at first with no one on second. As soon as the pitcher winds up to throw to the batter, the baserunner on first begins his sprint towards second base. This causes the second baseman to be forced to move towards second base with the runner, creating a gap on the right side of the field towards which the batter tries to hit. If the hit and run is effective, the baserunner and batter should be able to avoid the double play and the runner from first should be able to make it to third base.

Infield Fly Rule: Whenever there are less than 2 outs and there is a force play at third, if a batter hits a pop fly in the infield he is called out whether or not the infielders actually catch it. Any fair fly ball that could have been easily caught by an infielder with ordinary effort is covered by the rule. The rule is intended to prevent the guys on defense from being able to make a super-easy double or triple play.

Luxury Tax: A tax on teams that spent the most on payroll. Each year a “threshold” is set, and teams that spent more than that amount were taxed a percentage of the amount over the threshold that they spent (first-time offenders paid a 17.5% tax on their overage in 2003, 22.5% in 2004 and 2005, and none in 2006; 2nd-time offenders had to pay a 30% tax in ’04 and ’05 and 40% in 2006; 3rd-time offenders paid 40%).

Unlike

Revenue Sharing, the luxury tax money does not benefit any of the teams. Half of the money goes to player benefits (i.e. pension fund), one quarter of the money to the industry-growth fund, and the last quarter is allocated for developing baseball players in countries with no organized baseball at the high school level.

Moneyball: Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game is a book written by Michael Lewis that explores the methods of A's general manager Billy Beane. Billy and the A's have a somewhat innovative way of evaluating baseball players that helps them identify young and inexpensive talent that other teams miss. While most ball clubs evaluate potential players by placing a high value on batting average, RBIs and home runs, Billy Beane pays close attention to on-base percentage - a good estimate of a player's ability to avoid getting out -and extra base hits. Beane uses the A's low payroll to its best potential by selling off high paid stars and acquiring overlooked players with strong OBPs and good extra base hit numbers.

Essentially, the "Moneyball Management" philosophy aims to place statistics over scouting, and to take advantage of skills that are undervalued by the rest of the market. The most telling sign of Moneyball's influence is that some teams have started to appoint Ivy League graduates with minimal baseball experience to top positions, thanks to their ability to analyze statistics.

OPS: An index used to evaluate batters. It stands for "on-base percentage + slugging percentage". Since it evaluates a player's ability to get on base and his ability to hit for power, it is often a better assessment of a batter's production value than batting average. An impressive OPS is one over 1.000 - in 2006, David Ortiz had a 1.049 OPS, Manny's was 1.058, and Ryan Howard's was 1.084.

Pavano: This term can be used in a number of ways:

Noun.

- A chronically injured baseball player: Carl Pavano has been a pavano for most of his time with the Yankees.

- A money pit requiring millions of dollars and offering little return: Wow, this old fixer-upper house we bought sure is turning out to be a pavano- we've been working on it for years and it's still not habitable!

- An unwanted long-term commitment: I had to sign a lease for my apartment; it’s a total pavano since I can’t move for a year even though I found a cheaper, more attractive place to live.

Verb

- To injure oneself in a strange, unconventional manner: I pavanoed when I tripped over a pile of cotton balls, fell into a large trampoline, and catapulted onto the roof of my dog’s house; I broke my left leg, 3 ribs and my right pinky finger.

- To disappoint people; not live up to expectations: I did not want to pavano, so I showed up to work early on my first day and worked late on a special assignment.

- To avoid manual labor at any cost, including inflicting injuries on oneself to disqualify one from performing said labor: Jimmy was sick of his tough job as a carpenter, so he pavanoed by intentionally contracting avian flu.

PECOTA (not the player!!): An acronym for

Player

Empirical

Comparison and

Optimization

Test

Algorithm. A system using sabermetrics (*definition coming soon*) to calculate projections for players and teams. The exact formulas that are used are apparently top secret, but they are very advanced, capable of forecasting everything from improve rates of individual players to total team wins. As far as accuracy goes, PECOTA has proven to be a great indicator or future performance. For example, in 2007 they projected the Yankees would win 93.3 games; they ended up winning 94. PECOTA is very popular amongst fantasy baseball players, as it helps the "team managers" to draft players that are projected to do well the categories that are generally used such as OBP.

Pickle: AKA "Rundown". A situation in which a baserunner is caught between two bases. Most often a pickle situation begins when a runner attempts to advance to the next base on a ball hit by his teammate and is cut off by one of the defensive players. The baserunner, seeing that he won't be able to make it to the next base as he had planned, must attempt to return to the base he ran from without being thrown or tagged out. The defensive players - generally basemen - throw the ball back and forth, forcing the baserunner to go back and forth between the bases until the defensive players either tag him out or make an error allowing the (very lucky) baserunner to reach one of the bases safely.

Relief Pitchers: Closers vs. Set-up men vs. Middle Relievers vs. Long Relievers: As far as official position titles go, a pitcher is a pitcher is a pitcher. However, managers use different pitchers at different points in the game to use each player's talents to their maximum potential. A closer is the pitcher generally brought into the game in save situations (see

save definition) and a set-up man is the pitcher brought in right before the closer, usually in the 7th and 8th innings. Middle relievers, shockingly enough, pitch in the middle innings of the game. Long Relievers are ones you hope not to have to use - - they come in when a starting pitcher gets beat up on early in the game (not that that would ever happen to a Yankee…)

Revenue Sharing: The idea behind the revenue sharing agreement is to create a more even playing field (no pun intended) between the teams with the most money and the smaller-market teams. Each year the top 13 revenue generating MLB franchises contribute to a community pool that benefits the bottom 17 revenue generating franchises; the amounts the teams pay or receive are dependent on the amount of “net revenue” – which is the amount of money they took in minus the “operating costs” of the team – a team earned that year. The money that the “payee” teams receive is intended to be used for “on-field improvements”, AKA payroll, but there is nothing specifically stating how the money is required to be used in the CBA.

RISP: This stands for "

Runners

In

Scoring

Position" and is a measure of how well players hit when their teammates are in scoring position (on 2nd or 3rd base). It is calculated exactly the same as batting average (# of hits divided by # of at-bats) except

only at-bats when runners are in scoring position are taken into account.

Sacrifice: AKA "Sac". A ball hit when there are less than two outs for the sole purpose of advancing a baserunner. The batter hits with the intent to advance his teammate while knowing that he himself will be called out. For instance, in the case of a sacrifice fly, the batter hits the ball high and deep, and once it is caught the baserunner tags up and runs to the next base. Pitchers often use a sac bunt when they come up to bat, knowing that the defense throw them out at first while their teammate is able to run to second. Sacrifices are not counted in a player's average, so hitting sacrifices will not lower a player's batting average.

Safety Squeeze: Essentially, a play in which a runner at third scores on a sacrifice bunt by his teammate. Unlike the Suicide Squeeze, where the runner at third begins his sprint towards home while the pitcher is winding up, in this case the runner won't begin heading home until the batter has made contact with the ball. The hope is that batter's bunt will land in a location that will make it difficult for either the pitcher or the catcher to field and tag the runner out at home in time to make the out.

Save: We've watched Mariano, Trevor and Gagne make headlines with their save numbers, but what exactly is a save? There are several conditions that must be in place in order for a pitcher to be credited with a save. Most importantly - and most obviously - a pitcher can only earn a save in a game that his team has won. In addition, the pitcher earning the save cannot also be the pitcher that earned the win for the team. Finally, the pitcher must fall into one of the following three conditions:

a) The "saving" pitcher enters the game when his team has LESS than a three-run lead and pitches for at least one inning. In keeping with this rule, a pitcher cannot "create" his own save situation - - if he enters the game with a six run lead, he will not be eligible for a save even if he ends up giving up four runs.*

or

b) The "saving" pitcher enters the game with the opposing team's tying run either on base, at bat or on deck, and maintains the lead.

or

c) The "saving" pitcher pitches effectively (i.e., doesn't give up the lead) for three innings.

Using saves to evaluate a pitcher is a relatively controversial topic. Many people (Yankees Chick included) feel that it is a bit arbitrary and that WHIP and ERA are more accurate. For reference, however, the top five all-time save leaders after the 2007 season are:

Trevor Hoffman (Marlins, Padres): 524

Lee Smith (Cubs, Red Sox, Cardinals, Yankees, Orioles,Angels, Reds, Expos): 478

Mariano Rivera (Yankees): 443

John Franco (Reds, Mets, Astros): 424

Dennis Eckersley (Indians, Red Sox, Cubs, A's, Cardinals): 390

*

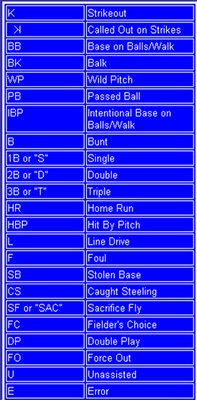

note: Even though a pitcher can't create his own save situation, he can earn a win for his team if he blows a save and his team comes back and wins. For example, if Mariano were to come into the game in the top of the 9th inning with the Yankees up by 2 runs, and let the opposing team tie the game, he would be credited with a "blown save". However, if the Yanks scored a run in the bottom of the ninth to win the game, Mariano would also earn a "win" in addition to the blown save!Scorekeeping Abbreviations: If you're not familiar with all of the scorekeeping jargon, a major league scorecard could look like a foreign language. Luckily, with a keen eye one can see that there are only a few different abbreviations to remember in order to decipher what the heck the announcers are referring to!

The first things to memorize are the numbers associated with each position on the field.

For example, if a batter grounds out to the second baseman and is thrown out at first, the play would be noted as "4-3" groundout.

Next are the symbols for different plays, most of which are pleasantly simple:

For example, if Randy Johnson hits Jeremy Reed with a pitch, scorekeepers will mark "HBP" in the spot for Reed's at-bat. Or, consider a situation in which Manny Ramirez hits the ball to Robinson Cano at second with BoSox teammate Renteria on first. Cano, thinking fast, whips the ball over to Jeter (who is covering second base, of course) to get Renteria out; Jeter, then, throws the ball over to Giambi to get Manny (who was nowhere even close to running it out). The beauty of scorekeeping symbols allow us to abbreviate that play by calling it a "4-6-3 DP”.

Small Ball: An offensive strategy that focuses on getting runners on base and moving them into scoring position without aiming for extra base hits and homers. Plays such as bunts, sacrifice hits, stolen bases, and hit-and-run plays are used to "manufacture" runs. The keys to small ball could be summed up as speed, aggressive baserunning and "productive outs" (those sacs I mentioned). One situation where you might see this strategy employed would be a situation in which the score was tied in the bottom of the ninth inning and a couple players without much pop are due up to bat -- the first man might lay down a bunt then steal second base, then the manager would call for a hit-and-run play, followed by a sac fly by the third batter up, etc.

Suicide Squeeze: Similar to the

Safety Squeeze, but even more difficult to carry out. The man on third begins his sprint for home as soon as the pitcher begins his wind-up - this way, no matter where the batter's bunt falls, it will be nearly impossible for the defense to make a play to get the runner at home. On the other hand, if the batter fails to make contact with the ball, the runner is almost certainly going to be caught. This play's success is entirely dependent on surprise and perfection - - the defending team must have no idea that a squeeze play is in the works, and the batter must make contact with the ball, no matter how poor or difficult the pitch looks.

Tommy John Surgery: AKA "Ulnar collateral ligament replacement procedure”. Named after the pitcher for whom the surgery was created in 1974. The surgery serves to correct damage to pitching (or throwing) elbow, which occurs when the ligament frays or detaches after overuse and perpetual overextension. The surgeon uses a non-needed "donor" tendon from the patient's hamstring, leg, or non-pitching arm and threads it through holes drilled through the elbow, essentially re-crafting the pitcher's joint. In successful cases, which account for about 80% of all patients (depending on which doctor you ask), it generally takes at least one year for a player to fully rehab and start pitching to full capacity again - often faster and harder than they ever had before the surgery. In John's 12 pre-surgery seasons he hit a high mark of 16 wins in a season and an average ERA of about 2.92. After rehabbing from the surgery, he continued to play for sixteen more seasons with an average ERA of 3.9 and twice won over twenty games.

Walk-Off Hit: If the game is tied or the home team is down by a few runs in the bottom of the 9th (or later) inning and a batter gets a hit that knocks in enough runs to put their team on top, that is known as a "walk-off" hit. It is called a "walk-off" because it ends the game. For example, if the Red Sox and Yankees are tied in the bottom of the 9th inning at Yankees Stadium and Jorge Posada hits a solo homer to put the Yanks on top, the game ends right then and there. No one else needs to bat, and the other team doesn't get another chance (since it was the bottom of the 9th inning). A walk-off hit cannot occur in any inning earlier than the 9th (since the game cannot end earlier than the 9th inning), and a visiting team can not win with a walk-off hit (since the home team always has a chance to bat in the bottom of the inning).

WHIP: A ratio used to evaluate pitchers. It stands for "walks + hits allowed per innings pitched". It is considered by many to be a better gauge than ERA when evaluating a pitcher's effectiveness. For instance, if a pitcher consistently allows batters to get on base, this will be reflected in his WHIP, but not necessarily in his ERA - - his ERA will only be inflated when earned runs come in. While no statistic is perfect, WHIP is less affected by the pitcher's backing defense than ERA is.